Freeze

Two years ago, I blew out my knee in a skiing accident.

About six months ago, I went rock climbing with friends and my daughter.

I was nervous about the knee, but started up an easy route.

And then something happened.

I froze — about a quarter of the way up.

I rested, tried again, and made it halfway…

then froze again.

A third attempt — three-quarters of the way up —

and I froze once more.

I’ve rock climbed before.

Before the injury, I made it to the top.

So what happened?

I’ve always had some fear of heights, but this was different.

This was a full freeze response.

I suspect it had something to do with the knee injury —

the trauma of falling, of getting hurt, of losing trust in my body.

Yesterday I wrote about courage.

And courage did show up here — I kept trying.

Each time, I went a little further.

But each time, I still froze.

And freezing leaves a terrible taste in the mouth.

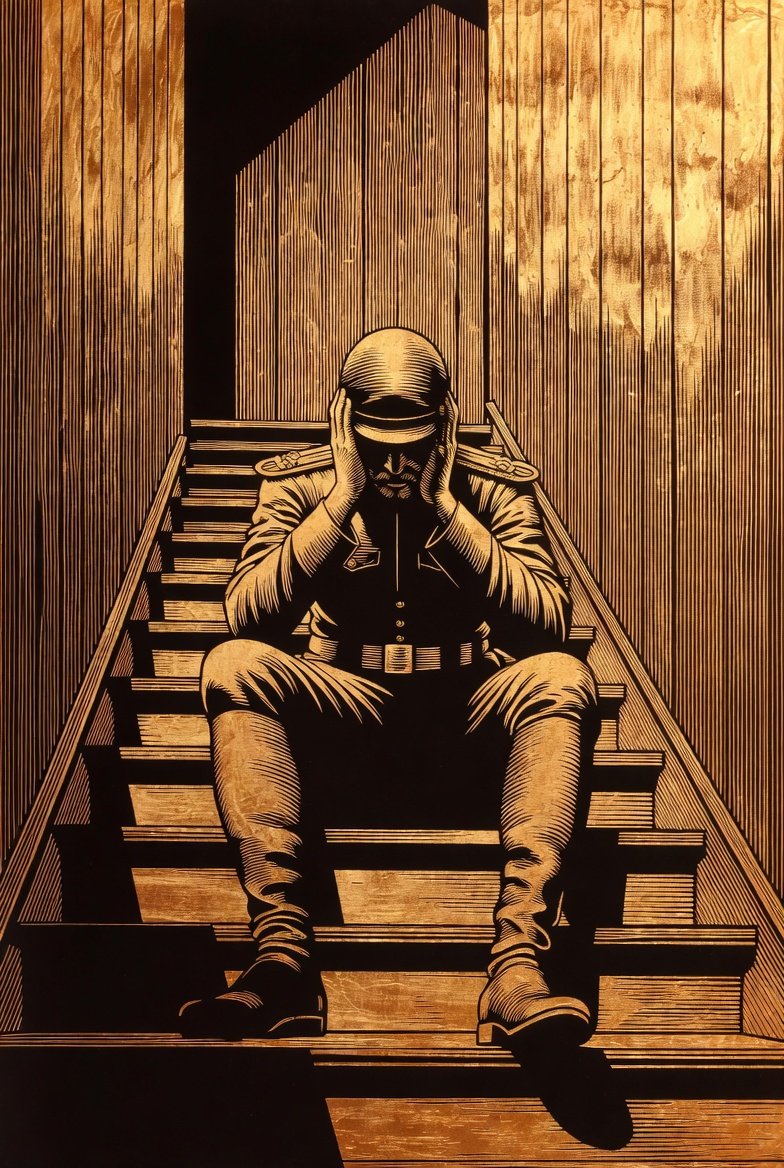

That’s why the character of Corporal Upham in Saving Private Ryan haunts me.

Upham argues for mercy for a captured soldier.

Later, that same soldier returns and kills one of Upham’s companions —

while Upham freezes on a stairwell, unable to move.

That scene enrages me viscerally.

And yet… I’ve frozen too.

Sometimes dramatically, like on the climbing wall.

Other times in smaller ways — not fully showing up, not speaking, not acting.

Depression itself can be a form of freeze.

What’s important to understand is this:

no amount of self-judgment fixes a freeze response.

Upham wants to help his companion.

He wants it desperately.

But no amount of willpower can make his body move.

That’s what makes the scene unbearable.

This is terrifying for any person to contemplate —

because all of us carry hidden traumas that can surface at the worst possible moments.

I remember a small moment from my childhood.

In 1981, my mom was at a grocery store and scratched a “scratch and win” card.

She won $10 and lit up with joy.

A woman nearby said bitterly,

“Why are you so happy? You’re rich. You don’t need $10.”

My mom froze.

Tears welled in her eyes.

She hurried out of the store, dragging me with her.

Years later, she still carried regret —

not because the comment mattered,

but because she had frozen and said nothing.

So not all freezes are dramatic Upham moments.

But almost all freezes — big or small — leave behind the same residue:

regret, shame, self-loathing.

Yesterday I wrote about courage and said something harsh but true:

that some deaths happen on the battlefield,

and some happen quietly inside.

But what happens after a freeze?

What happens when you don’t rise?

When your body betrays you?

When you hate yourself for it?

Because here’s the truth most men don’t want to face:

Most men aren’t afraid of dying.

They’re afraid of freezing when someone they love needs them —

and then having to live with themselves afterward.

And that leaves us with the real question:

What do we do next?